Opening the Door

The door of social change is heavy and, when it does open, it often does so with a complaining screech.

Gaining admission to the bar today is seen by many as a difficult process, as it requires three years of post-graduate education, the successful completion of a two-day exam and a character and fitness evaluation. These hurdles would have been welcomed by the first African Americans and women who sought to enter the legal profession because, at that time, there was not a uniform procedure for admission to the bar. Instead, local judges and panels evaluated candidates and used the unfettered discretion vested in them to deny admission to qualified applicants based on race and gender.

In addition to the tainted admission process, African Americans and women faced other obstacles. For example, African American lawyers were excluded from white bar associations, requiring them to start their own. Beyond such institutional racism, they also faced violence and intimidation tactics.

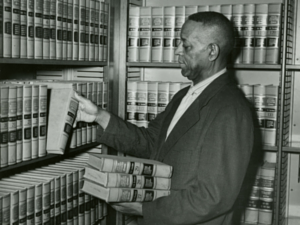

In 1960, segregationists bombed the home of prominent African American lawyer, Z. Alexander Looby because they were outraged by his civil rights work. The blast was so strong it nearly leveled the Loobys’ home and blew out 140 windows at nearby Meharry Medical College.

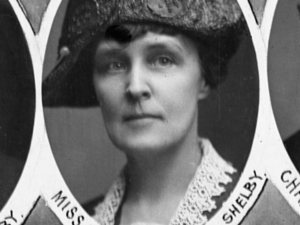

The plight of hopeful women lawyers is exemplified by Marion Scudder Griffin’s struggle. Despite being certified to practice law by two local judges and passing the bar examination, the Tennessee Supreme Court denied her admission to the bar not once but twice. Both denials were premised on her gender. Undeterred, she lobbied the Tennessee Legislature to pass a statute permitting women to practice law. Initially met with “wisecracks and guffaws”, her lobbying efforts were eventually successful. Only then did the Tennessee Supreme Court allow her to practice.

In the following decades, both African Americans and women made tremendous strides in the legal profession and now serve our communities as successful lawyers, law professors, legislators, judges, justices and chief justices on the State’s highest court. With our two new alcoves on African Americans and women, the Tennessee Judiciary Museum hopes to educate Tennesseans, young and old, about those who opened the door.

-

Z. Alexander Looby

-

MARION GRIFFIN

-

Aaron taylor